At the end of the First World War, the French army sought to lure German planes towards luminous targets that would imitate Paris landmarks. French newspaper Le Figaro has uncovered archives detailing the proposed procedure.

Almost a century after the start of the First World War, this incredible project of the French Armed Forces remains a very little known one to this day. In 1918, as the conflict was coming to an end, the DCA (the organisation charged with defending French territory from aerial attacks) launched itself into the construction of a replica of Paris designed to dupe the German pilots. Aeroplanes, which had made their entrance into the armed conflict for bombing and tactical reconnaissance missions, were yet without radar. In creating a false town composed of a myriad of lit installations, the French hoped to attract the nocturnal raids towards the wrong targets.

A British blog site recently brought to light an edition of the magazine Illustrated London News from November 1920, which detailed the incredible passive defence plan that was put in place to to defend the French capital. From here, a number of other publications took up the story, with Le Figaro managing to unearth even more archive material on the ambitious project.

Although lighting had already been used to find bombing targets, the first experiments using lighting to create the impression of false targets were started in 1917. German Gotha bombers had already begun their first tentative bombing raids on London, so the threat to the French capital was a real one.

The project began with “a few acetylene lights arranged to give the impression of the presence of of unlit avenues”. At the urging of Secrétariat d’État à l’Aéronautique (Secretary of State for Aeronautical) and the DCA, the project was substantially upgraded in 1918 and the decision was taken to not only imitate a few streets but the entire City of Light.

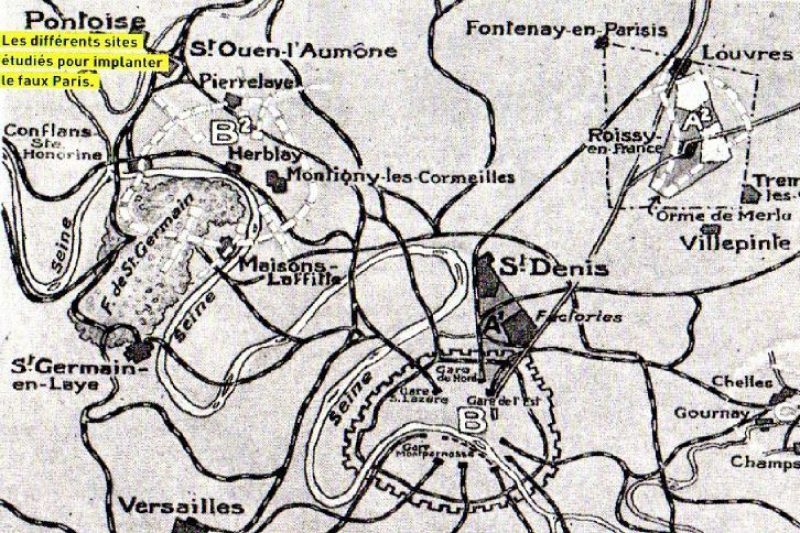

The challenges in bringing the plan to fruition were difficult, to say the least: they had to find curves in the River Seine similar to those found in the capital that were well away from any built-up areas.

Three sites were chosen. Installation began with Zone A2 near Villepinte (drawing courtesy of French Military Review).

The DCA didn’t possess the means to carry out the big plan themselves and the job had to be contracted out to a private company. An electrical engineer of Italian extraction – Fernand Jacopozzi – was hand-picked by agents of the French administration to head the project. Jacopozzi was chosen for the Tintin-esque adventure, according to Le Figaro, because of “his ingenuity and the simplicity of his method”.

Attract without Arousing Suspicion

First false target on the list was the Gare de l’Est; situated between the north-eastern suburbs of Seyran and

Villepinte. This project consisted of buildings, departure tracks, stationary trains, moving trains, signals and a factory with ancillary buildings and furnaces burning. The wooden buildings were covered with painted cloth, stretched and translucent so as to imitate the dirty glass roofing of factories. The main difficulty rested in the intensity of lighting required. They had to attract the attention of the enemy pilots but not so much as to arouse their suspicion.Jacopozzi seems to have taken on this challenge with gusto, using “lamps of different colours (white, yellow and red), illuminating alternately artificially-produced smoke” to imitate the glow of machinery in operation. Trains were represented by wooden surfaces on the ground. Lateral lighting was projected outwards from the “carriages” as if it were coming through the windows of a train.

The pièce de résistance, however, was the reproduction of a moving train. The camouflaged area was extended over a 2km length and the lighting moved progressively from one end of the site to the other and back again.Unfortunately, all of this painstaking work was in vain, as the installations weren’t finished until after the last aerial raid on Paris in September 1918. “They were therefore not put to the test in a real situation”, as a military review soberly puts it in 1930. It was later discovered, in fact, that the Germans had a similar plan in mind.

For Jacopozzi himself, the enormous lighting project was far from a waste of his time. Believed to have been handsomely paid for his services to the Republic, the same engineer was to undertake the project of illuminating the Eiffel Tower (the real one!) for the first time a couple of years later, as well as lighting up various other Parisian landmarks including the Champs-Élysées.

Tootlafrance is Ireland’s fresh new eyes on France, bringing you the latest news, exclusive celebrity interviews, political analysis, cultural events, property news and, of course, travel features written by top Irish journalists.

Tootlafrance is Ireland’s fresh new eyes on France, bringing you the latest news, exclusive celebrity interviews, political analysis, cultural events, property news and, of course, travel features written by top Irish journalists.